The map, Deleuze and Guattari insist, “fosters connections between fields (Deleuze and Guarrari, 2004: 13). Mapping is a creative activity, where memory and imagination occupy center stage. In spite of the emphasis on the trope of the journey with a map that suggest one can read and interpret the landscape, Munro does not engage in any realistic description of the landscape in “What Do You Want to Know For?” For Munro, who describes kame moraines as “wild and bumpy with a look of chance and secrets” (Munro 2006: 321) acts as a “geomancer” (McGill, 2002: 109), one who composes the landscape as she maps it. As she reads her maps and the landscape, claiming to uncover realities or pointing to disregarded features, it is soon quite clear that Munro is not simply depicting a landscape, instead engaging in an experimentation in contact with the real. In the introduction to A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari oppose tracing (le calque) and the map: “what distinguishes the map from the tracing is that it is entirely oriented toward an experimentation in contact with the real” (Deleuze and Guattari, 2004: 13).

With the maps, she points to visible features of the landscape and conjures up the hidden features of the glacier landscape the maps help her to identify, she describes actual landscape and recalls absent landscape.

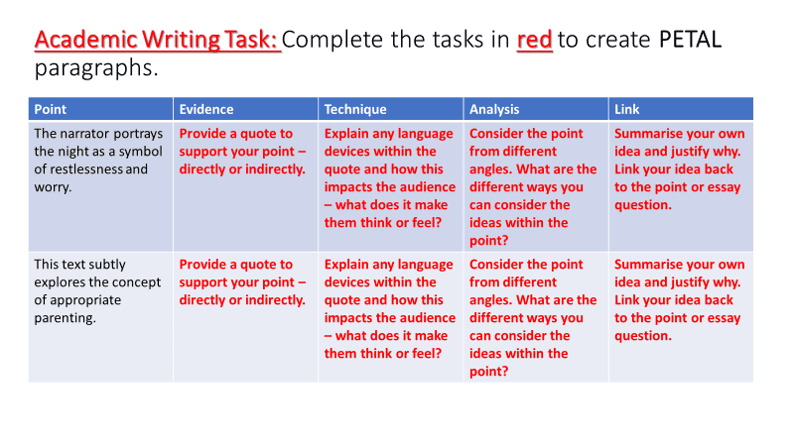

These maps show both the usual towns, roads and rivers and geological features of the Ontario countryside. Munro, as persona and narrator of “What Do You Want to Know For?” (Munro, The View from Castle Rock, 2006), encourages her readers to read the landscape with her as she and her husband drive through the Ontario countryside with “special maps” (Munro, 2006: 319).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)